The Magician Longs to See

Peter Cochrane’s interests in alchemy, experimental photographic techniques, interconnectedness, and specificity of place intersect in these prints and sculptures created for the Athenaeum. This exhibition comprises four distinct bodies of work which weave together ideas of humanity and our place in the natural world. In researching the Athenaeum’s history to prepare for the exhibition, Cochrane focused on the history of the surrounding flora, from a majestic Torrey Pine which once stood guard at the Athenaeum’s entrance, to the species of roses Kate Sessions chose for a reading garden [in 1921] that has since been lost to history. Taking these as his starting point, he created two new series of photographic prints, burning the raw botanic materials to render these histories abstract. He expanded upon these prints with two sculptural series, showcasing our commonality with the blood-red manzanita tree, and how human innovation and mysticism has brought us to the element of lead throughout history. An undercurrent in Cochrane’s work emerges, highlighting our magical and mysterious relationship with nature, and each other. — Text by Christie Mitchell, Executive Director; and Jocelyn Saucedo Larson, Manager, Administration and Exhibitions; The Athenaeum

Below is a short video discussing each of the works comprising The Magician Longs to See

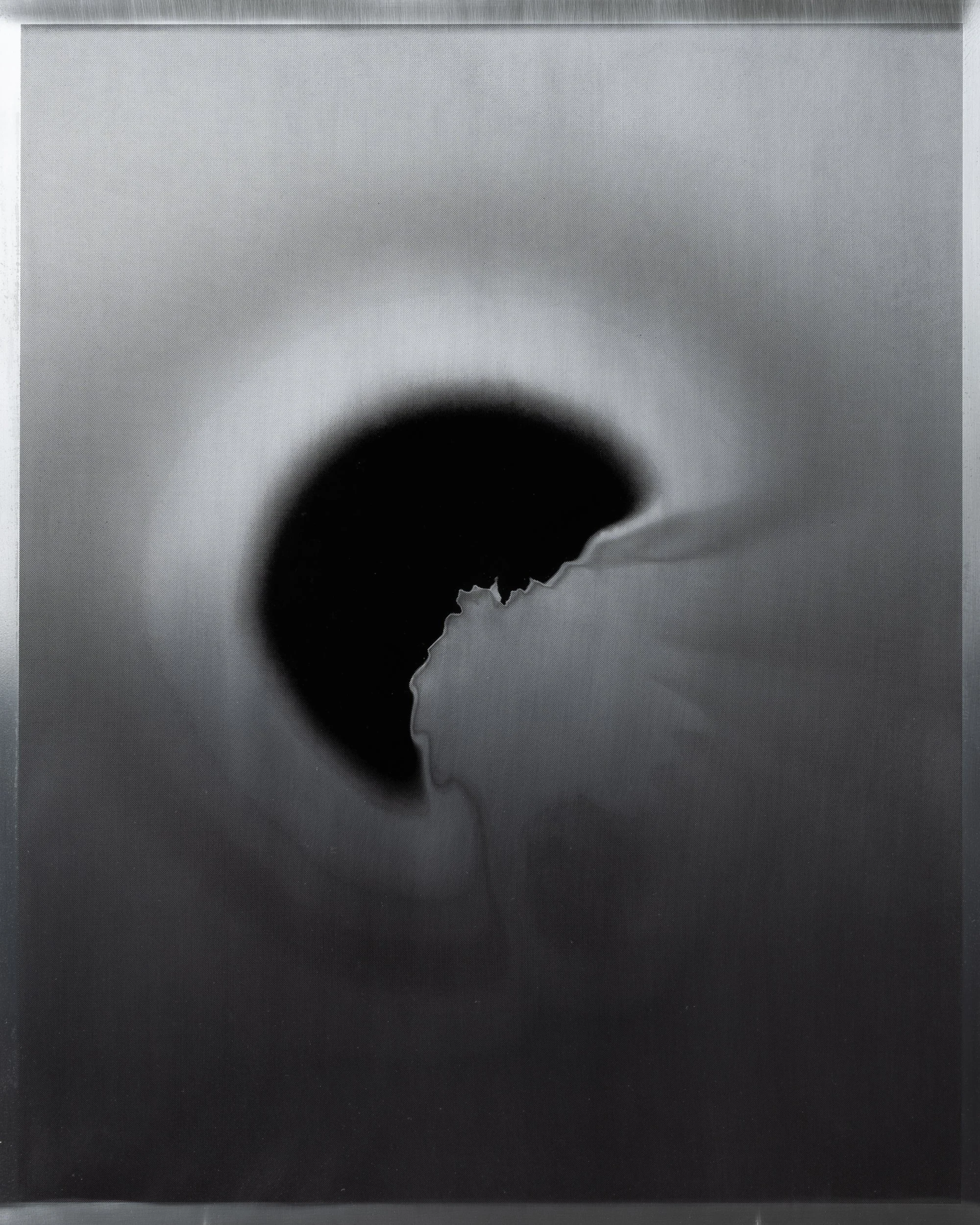

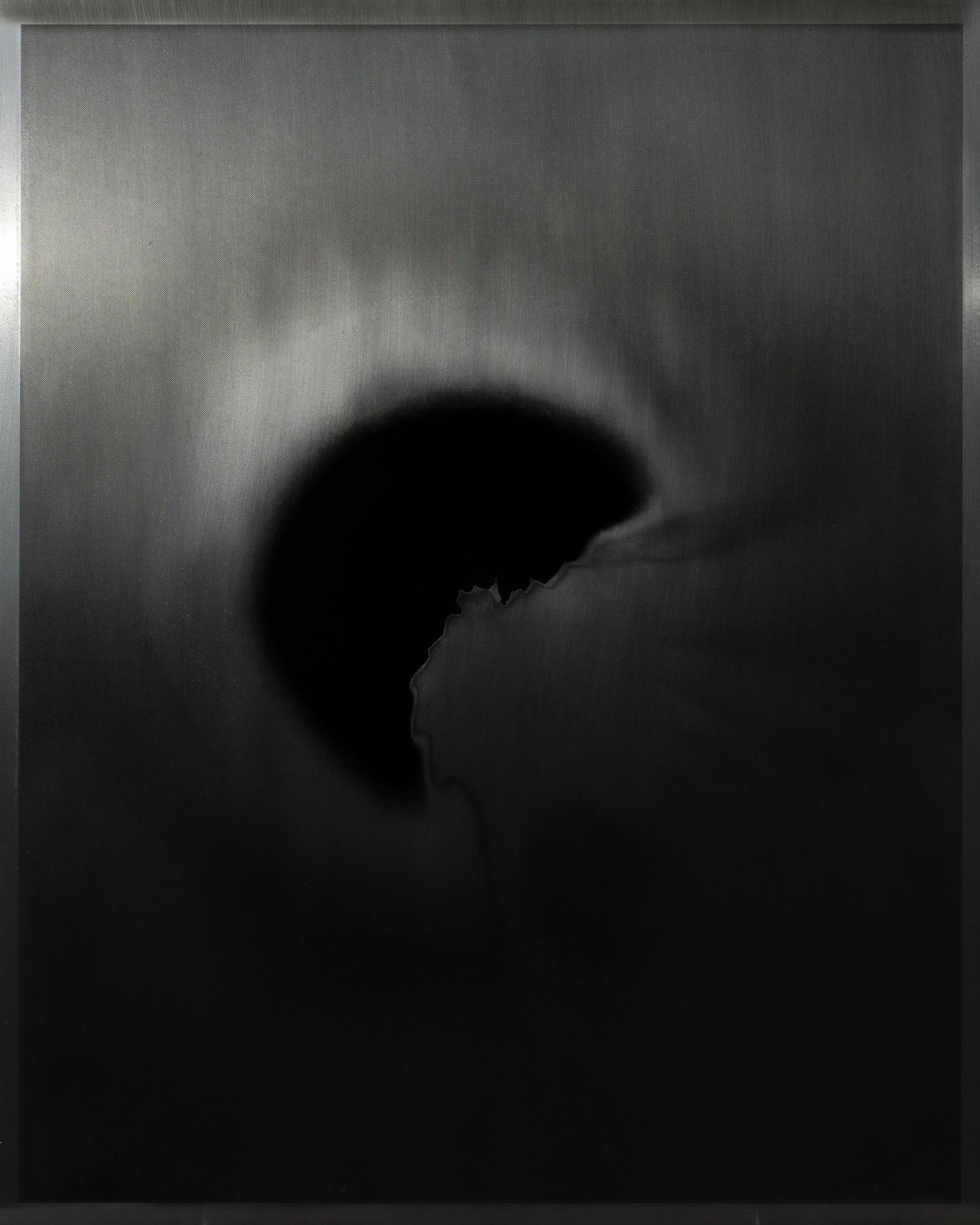

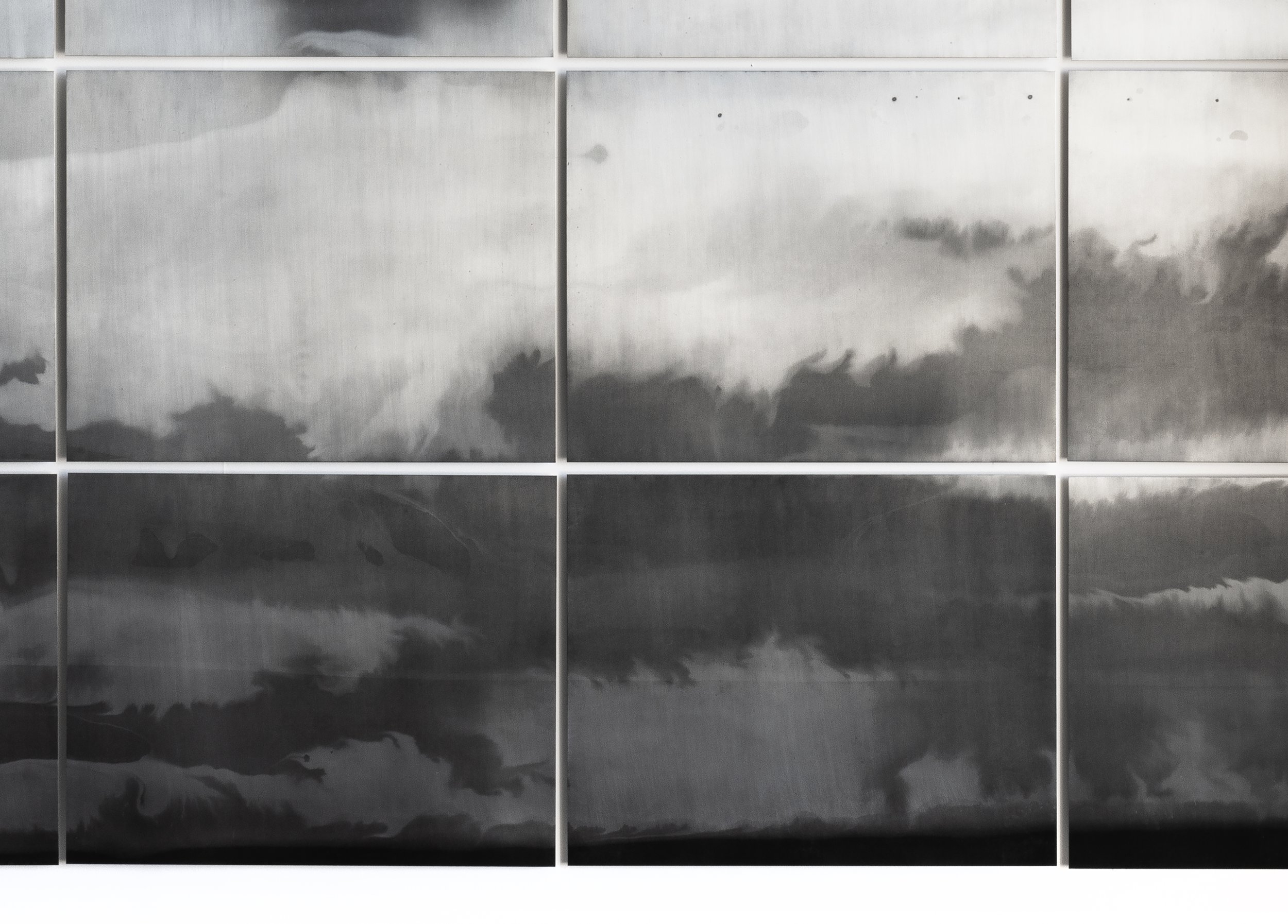

These etched zinc panels are created using two kinds of pinecones from two very different trees—the lodgepole pine that is ubiquitous across thousands of acres of the pacific northwest, and the critically endangered Torrey pine that survives only in the coastal regions around San Diego. The reproductive needs of these trees are diametrically opposed: The lodgepole pine cone matures to be encased in a resin and requires forest fires in order to break the seal and release their seeds. However, the Torrey pine is now under constant threat of extinction from wildfires that rampage across California. I grew up between California and Montana, and witnessed both the need for and fear of fire, so I turned to the darkroom to create traces of these trees. Like the creation of miniature universes, I set cones ablaze on silver gelatin paper, leaving only a trace fixed among silver halide crystals. To permanently affix these ghostly visions, I translated the images into etched zinc plates. What is seen is only metal, either raw or patinated, preserved under a coat of lacquer.

30 Panels, Torrey Pine

Zinc, lacquer

122.5”w x 82”h

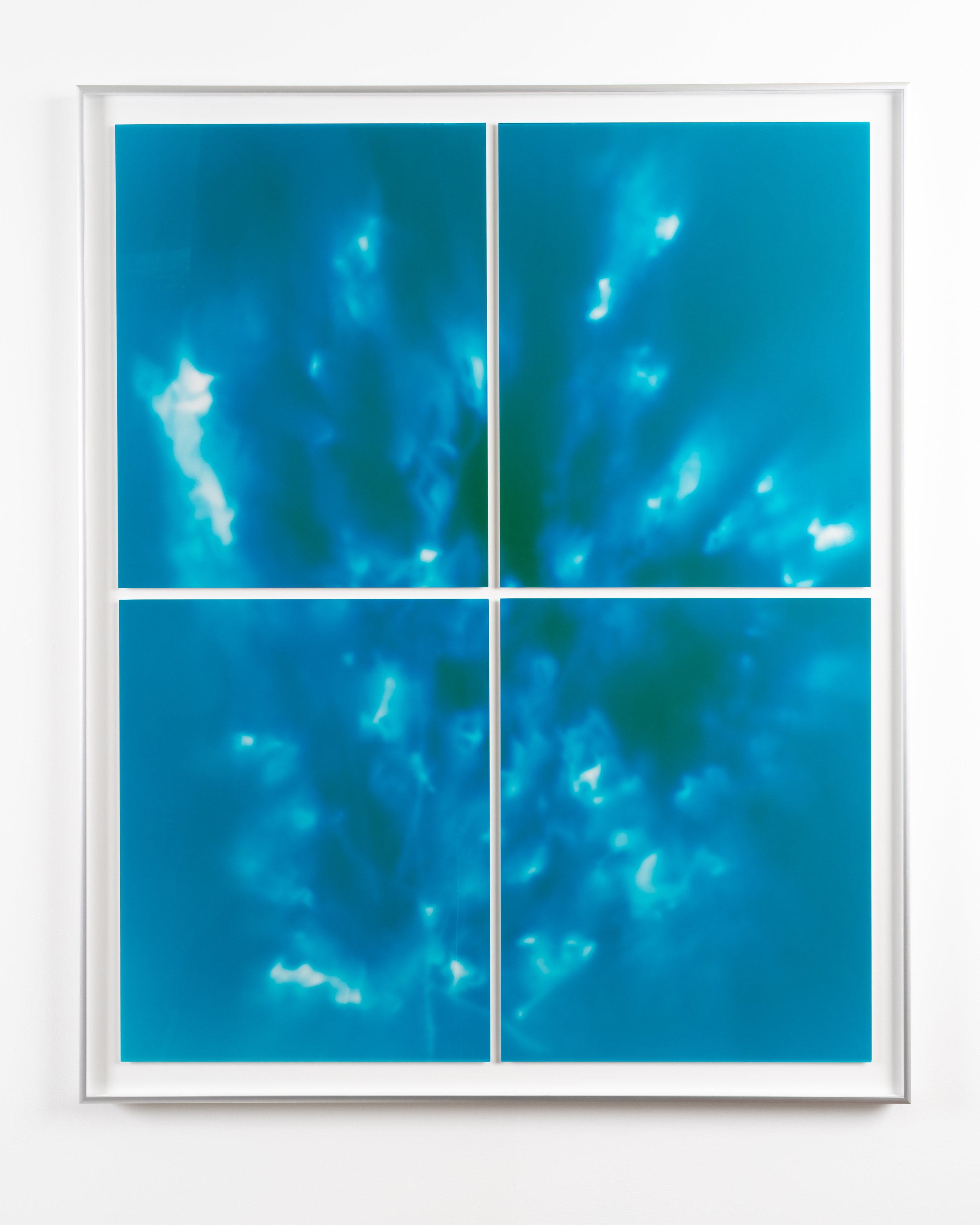

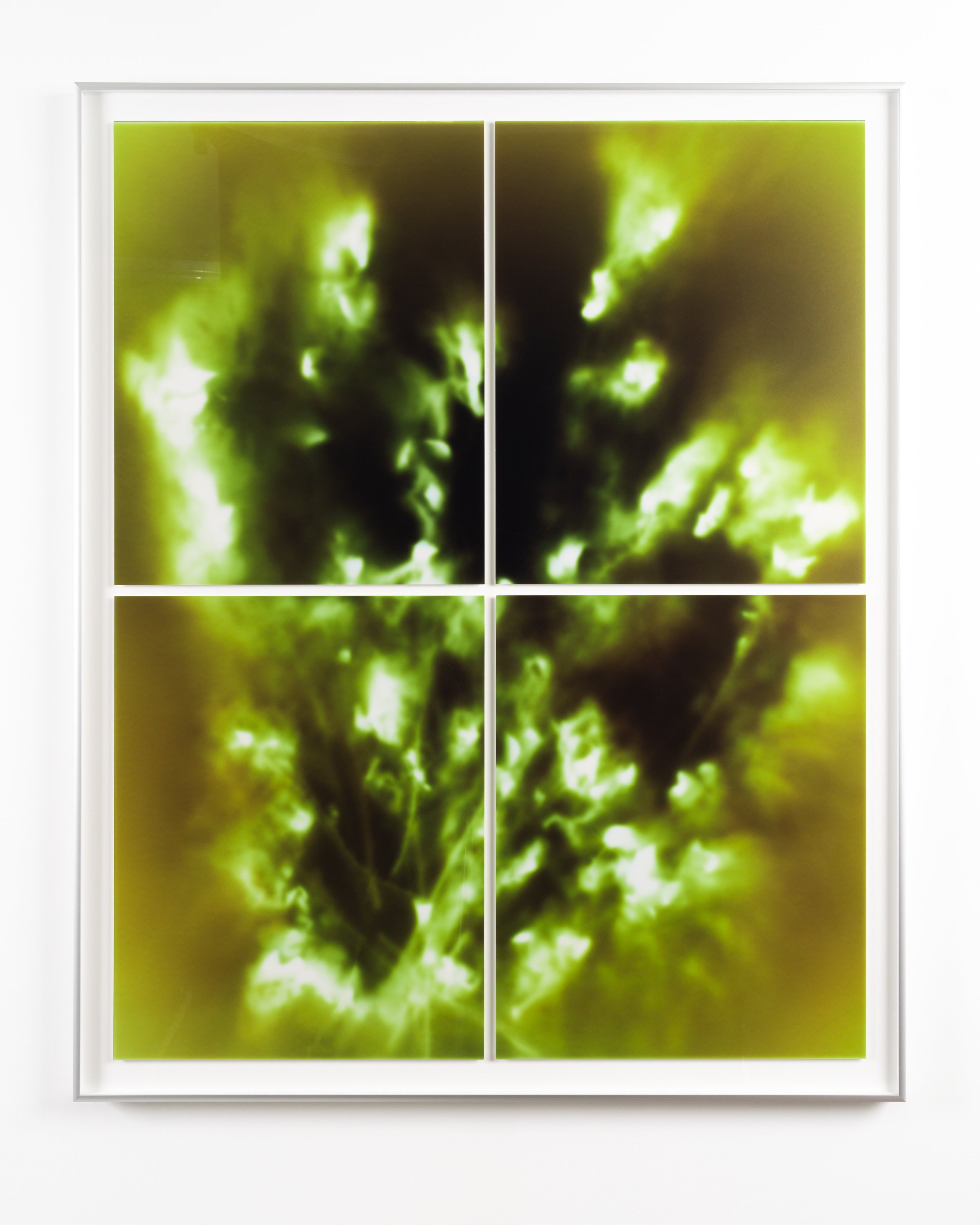

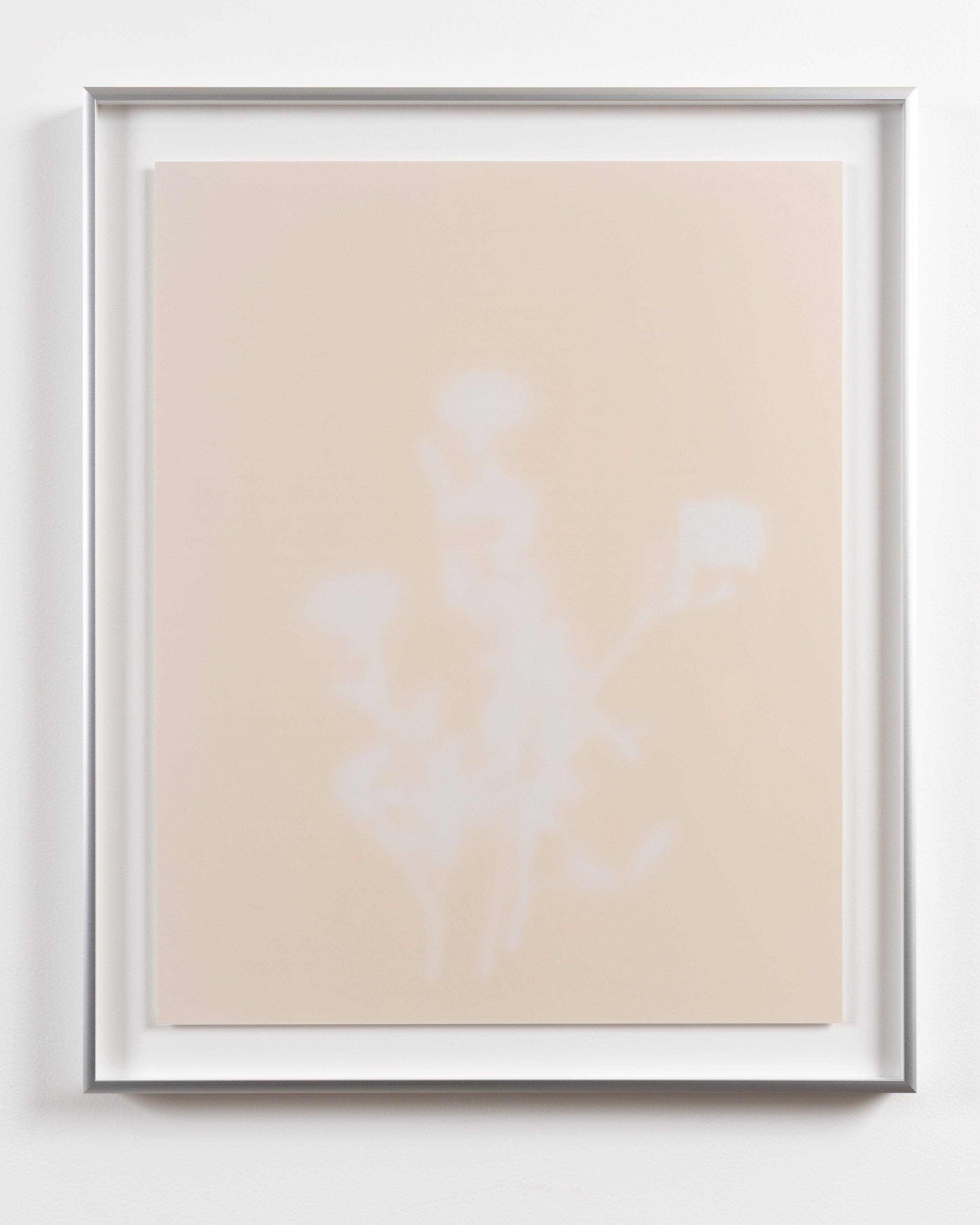

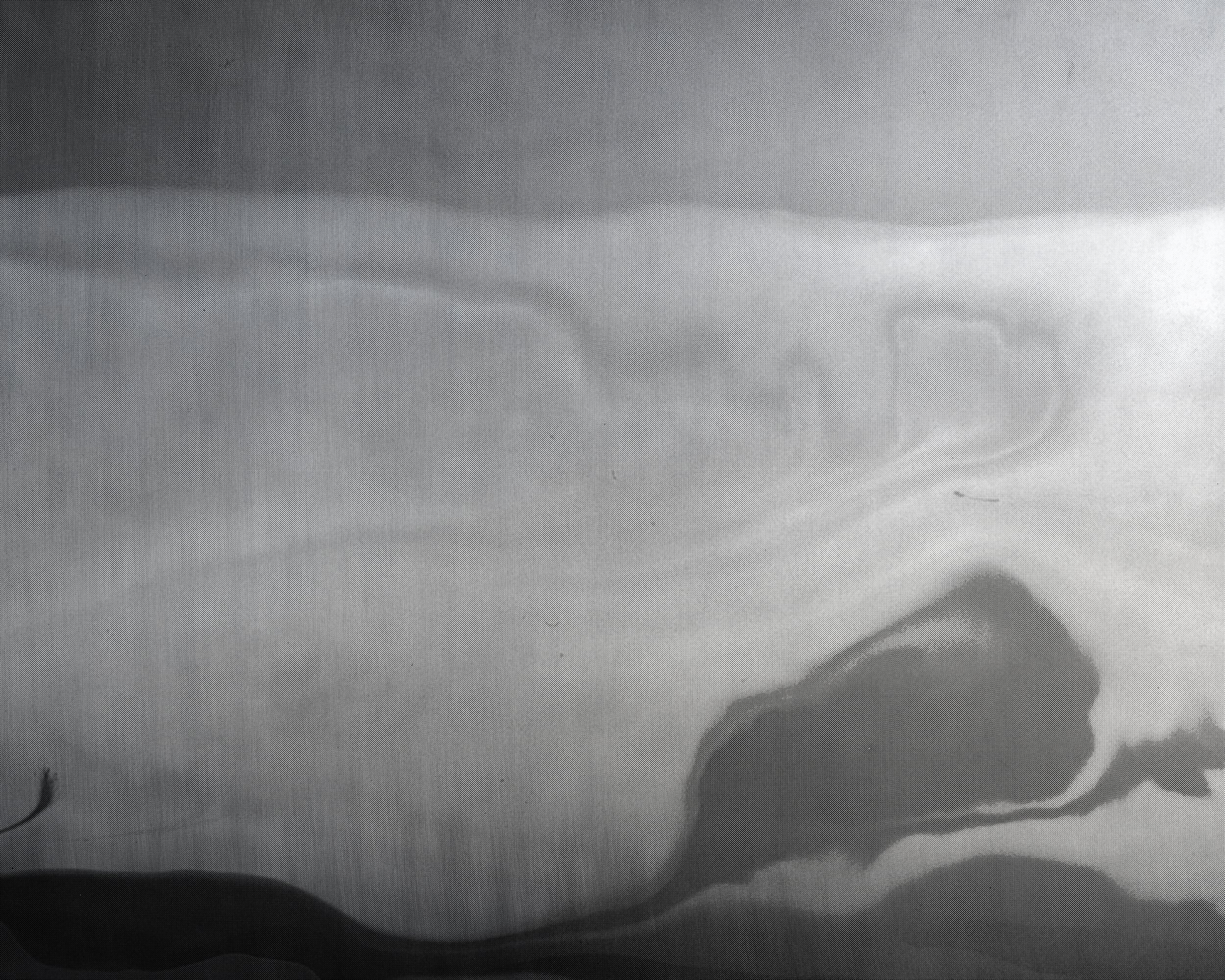

Looking through the archives of The Athenaeum yielded fascinating stories about the botanical life that once lived in and around the building. While a Torrey pine tree stood as a sentinel for the building’s front entrance, we found a planting guide from a garden renovation in 1921. Kate Sessions, a local, early advocate of native plantings and ecology, was commissioned to rejuvenate the grounds. Her list included two species of climbing rose: Cecil Bruner, and Thousand Beauty. I took to these flowers and used a similar technique as the black and white pine cone images—burning plant matter onto light-sensitive, color darkroom paper.

1: Climbing Rose - 4 Panel (Red)

2: Climbing Rose - 4 Panel (Green)

3: Climbing Rose - 4 Panel (Blue)

4x 16”w x 20”h (images)

35.5”w x 43.5”h (frame)

4: Climbing Rose (Purple)

5: Climbing Rose (Red)

6: Climbing Rose (White)

16” w x 20”h (image)

19”w x 23”h (frame)

Silver Halide Photograms

The manzanita tree has many parallel features to human beings, from its life span of around 60-100 years, to its blood red, smooth bark reminiscent of our own musculature. It can sustain through tough conditions like poor soil and high heat, but thrives as far north as British Columbia and as far south as Mexico. Like the big bang, or the spark of life, or the eternal flame from which we come and to which we will return, I wrap manzanita branches in golden thread, suspend them in space, and connect them to one another. Wherever we may have originated, we share basic atomic structures with each other, with inanimate objects, and with all things throughout the cosmos.

Lead is one of the most complex yet crucial elements that contributed to the success of human evolution. The theoretical transformation of lead into gold was the pursuit of alchemists across continents. The Romans devised early potable water and sewage systems out of lead pipes. Like arsenic before, its early use in paints now plagues homes, and lead paint must be carefully removed for fear of poisoning. Deadly when ingested or inhaled, it also has immensely protective qualities. Lead boxes are fashioned to hold spent radium and uranium used as nuclear fuel, or for the cleanup of radioactive material. Lead aprons are commonly used to protect our bodies from excessive x-ray exposure. Fascinatingly, certain variants of lead are formed through natural atomic decay of uranium, and measuring the uranium-to-lead ratios in our planet’s oldest rocks gave scientists the ability to deduce the age of Earth.

Lodgepole Pine

16”w x 20”h

Zinc, lacquer